AERIAL AND GEOPHYSICAL SURVEYS OF PROBABLE ROMAN AND PREHISTORIC FEATURES AT THE GASK FRONTIER TOWER OF RAITH, PERTHSHIRE

D.J.Woolliscroft & B.Hoffmann

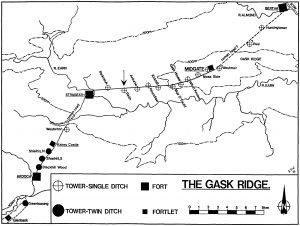

The site of Raith lies at NN 9319 1852, roughly half way along the known length of the 1st century Roman Gask frontier and approximately 170m to the south of the Roman road (illus 1). It stands beside an Ordnance Survey trig point on the western summit of the Gask Ridge itself (at a height of 91m) and constitutes one of the best observation points on the entire line. It has a spectacular field of view, taking in many miles of the Highland fringe to the north and west. To the south and southeast it looks right across Strathearn to the Sidlaw Hills beyond, whilst, to the east, it has the entire ridge top in view and is intervisible with every Gask Installation between the fortlets of Kaims Castle and Midgate. There have even been reports that it is intervisible with the glen blocker fort of Fendoch, c. 10 km to the north (e.g. Christison 1901, 28) but, in fact, the line of sight is thoroughly blocked by the 351m high Buchanty Hill

The site was discovered in 1900 when a pit sunk for the construction of a water tank revealed the four post holes of what appeared to be a Gask series watch tower, along with a quantity of unidentified red pottery (now lost). Fortunately, the features were noted by the antiquarian A.G. Reid and published by D.J. Christison (1901, 28). The report is brief in the extreme, just two short paragraphs, but it does tell us that the postholes survived to a depth of about 1 foot (0.305m) and formed a square with sides of 9 feet (2.745m). This would give a tower with an area of 7.54m2 which makes it the smallest on the system except for Gask House, which measures 7.44m2 (the average is 11.69m2, Woolliscroft 2002, 19 & 92ff). A great deal of decayed wood was found on the site and, unusually for the time, subjected to environmental analysis. The results were broadly comparable to those found on Gask towers in more modern times, with willow, hazel and oak fragments identified, along with a few barley grains. Some of the oak fragments were large and may have come from structural timbers, although sadly these have now disappeared.

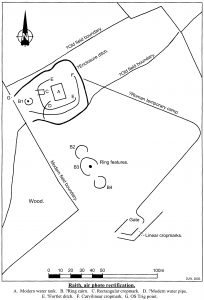

Since 1900 the site has been accepted into the roll of Gask system towers almost without question and, until recently, no further work had taken place. Indeed, it was assumed that the tower had been either totally destroyed or, at least, rendered permanently inaccessible by the water tank, which was covered by a considerable mound of earth. Objectively, however, the identification could not be regarded as fully proven. The site’s unusually large separation from the Roman road can be explained as a move to exploit the superb observation position, but the excavation encountered no sign of a ditch. Nor has any trace of a tower’s ring ditch ever shown from the air and the site is, in fact, generally unresponsive to air photography. There is, however, one superb, if neglected, air photograph in the Cambridge collection (neg AKD-96, see Woolliscroft 2002, 14, fig 1.9) which shows a number of other structures around the tank and suggests a previously unsuspected level of complexity on the hilltop. Few of these features have ever shown again, despite repeated reconnaissance in subsequent seasons by fliers, including ourselves. But a close study of the Cambridge photograph reveals a wealth of detail (illus 2).

A number of the crop marks seem likely to represent relatively modern features, including a number of old field boundaries, a small 8m x 5m open rectangle (illus 2, C) and a curving feature (D) which heads towards the tank and may be a modern pipe (although one might have expected a pipe to run straighter). Other marks appear to be much older. For example, at least four small ring features are visible. The smallest (illus 2, B1) is c. 7.3m in diameter and lies between the water tank and the trig point. The others lie in a rough line c. 60m to the southeast (B2 – B4) and, although incomplete and only approximate circles, measure c. 11m, 16m, and 12m in diameter respectively. Central maculae can be made out inside two of the features (B1 & B3), suggesting that they represent barrows containing cist (probably short cist) burials. If so, they parallel a cist barrow recently excavated by the writers at East Coldoch in Stirling, where a similar ditch break was found to be a real feature and not just an accident of crop mark formation (Woolliscroft & Hoffmann, forthcoming (a)). The other two ring structures show no central mark and might possibly be round houses. But in view of their close proximity to Feature B3 and the similarity of their ditch circuits, they seem more likely to be further burials whose cists have simply not produced detectable crop marks.

The air photograph also reveals two possible Roman structures. The first is the south-eastern sector of what appears to be a small Roman temporary camp. The corner itself shows clearly, along with a c.125m stretch of the southeast ditch. The northeast ditch appears only faintly, but a c.118m length can be made out with computer contrast enhancement. The two meet in a normal Roman rounded corner, but at an angle of just 72 degrees, rather than a right angle. In all, the detectable defences enclose an area of c. 1.47 ha (3.6 acres). No sign of an entrance is visible in the northeast ditch, but the southeast ditch shows a clavicula style gateway, c. 104.5m from the corner. This has been partly obscured by two linear cropmarks, but appears to be slightly non standard: having a somewhat elongated clavicula and possibly lacking the straight answering ditch projection of the classic Stracathro type gate (Jones and Woolliscroft, 2001, 92).

It is difficult to estimate the camp’s original total area, especially given the acute angle of the existing corner. Stracathro/clavicula gated camps vary greatly in their size, aspect ratio and gate positions and so one cannot simply extrapolate from the visible remains in accordance with a set plan. Such camps are, however, generally rectangular, rather than square and it is at least reasonably common for the short axis gates to be placed in the centre of the defences, whilst the long axis gates split the defences into roughly one third and two third lengths (e.g. Hanson 1987, 124). Given the overall lie of the land, which slopes away steeply beyond the western boundary of the modern field, one might expect the southeast defences to represent the long axis, with the visible gate roughly two thirds of the way to the southwest corner. If so, the total length of the southeast ditch would be around 157m. That would imply that virtually the whole of the northeast defences are visible, except for the corner itself, in which case the total area of the camp should be in the region of 2 ha (4.9 acres) over the ditch. This scenario seems unlikely, however, thanks to the absence of a visible gateway on the northeast side. Given the faint nature of the cropmark, it must be admitted that one cannot guarantee the absence of such a gate with any certainty, but it seems more probable that the southeast defences represent the camp’s short axis. If so, their total length should be around 209m and, if we assume that the long axis was approximately 20% longer (as seems about average for small claviculate camps in the area (Hanson 1987, 124)) at c. 250m, the overall size would be about 5.2 ha (12.9 acres) and the northeast gate should lie roughly 50m beyond the visible ditch sector. Naturally, none of this can be more than an educated guess, but both size estimates fall within the known size range of Stracathro type camps, which runs from c. 1.5 ha to more than 24 ha (Hanson 1987, 125). Moreover, a number of smaller camps are known on the Gask itself, albeit these mostly have different gate types. Examples include Gask House (Christison, 1901, 35), immediately to the south of Gask House tower, at c. 1.82 ha (4.5 acres), Easter Powside (Woolliscroft 2002, 29) at c. 0.45 ha (1.12 acres) and East Mid Lamberkin at 0.41 ha (1.02 acres), which does have one claviculate gate (Woolliscroft, 2002, 36).

The final crop mark is a playing card shaped ditched enclosure, whose long axis runs from southwest to northeast and which surrounds the modern water tank (illus 2, E). The air photograph does not show a complete ditch circuit, but the whole of the southwest and southeast sides are visible along with three of the four corners and parts of the other two sides. It is, thus, possible to project the entire outline, although whether this was actually completed only excavation or clearer air photographs will show.

At first sight, the feature resembles one of the Gask system fortlets and there had, in fact, been some reason to expect a fortlet in the vicinity, purely on spacing grounds. At present, three fortlets are known with certainty on the Gask: at Glenbank, Kaims Castle and Midgate (illus 1) and it is noteworthy that Glenbank is 6 Roman miles from Kaims Castle (and from the fort of Doune to the south), whilst Kaims is 12 Roman miles from Midgate. The possibility existed, therefore, that the fortlets were set out on a 6 mile spacing interval and Raith lies on the 6 mile point, half way between Kaims and Midgate. Furthermore, a fortlet at Raith would raise a still more interesting possibility. For it would then be conceivable that a fortlet and watchtower occupied the same site here. This may initially appear improbable, but there is a near precedent at the fortlet of Midgate, which has a tower immediately to its west whose ditch comes to within 13m of its own (Woolliscroft 1993, 303, illus 4). Obviously these two are unlikely to be contemporary, although both appear to belong to the first century line. They, thus, presumably mark a modification to the frontier at some point, in which a tower was replaced by a fortlet, or vice versa. Unfortunately, the two Midgate sites have no stratigraphic connection, since they remain just far enough apart that their ditch upcast does not overlap. It is, thus, impossible to tell which was built first. But if Raith does have a tower built actually inside a fortlet, it might well be possible to determine their relationship. This would be of great help in fleshing out the story of the frontier’s development and might also provide additional support for the growing body of evidence that the Gask was occupied for longer than had previously been supposed (Woolliscroft 2002, 3ff).

Alternatively, the presence of a fortlet raised the possibility that the structure found in 1900 was not a tower at all, but part of an internal fortlet building, especially given the absence of evidence for a tower ditch. This does appear unlikely, however, since no post founded building has yet been found inside a Gask fortlet. Indeed, although all three of the known Gask fortlets have been excavated, no internal building of any kind has yet come to light (Christison 1901, 18ff & 32ff and Woolliscroft & Hoffmann forthcoming (b)). Moreover, although the Roman Gask Project’s excavations at Glenbank fortlet found a substantial post founded gate tower, the Raith water tank post holes lay too far inside the ditch crop mark to represent an entrance structure.

There is, however, one major difficulty in accepting the Feature E ditch as a fortlet and that is its size. For when the Cambridge air photograph is rectified, the enclosure proves to measure c. 27.5m x 32.5m over the ditches, which is small by the standard of the other Gask fortlets. Kaims Castle, for example, measures 49m x 58m over its ditches, whilst Midgate is 42m x 48m. Glenbank is not directly comparable because, like all of the Gask installations to the south of Kaims Castle, it has a double ditch, but even its inner ditch measures 39m x 41m. The size of the fortlets themselves are rather more consistent on the system. Kaims Castle measures 20m x 22m internally, whilst Midgate is 20m x 23m (Glenbank’s ramparts did not survive well enough to be measured) and, since each has turf ramparts around 4-5m thick, their average external size of c. 28-30m x 30-33m would still not fit inside Feature E’s ditch. The issue may not be totally decisive, for smaller fortlets are known elsewhere, but the authors would now be less confident of this identification than hitherto. Interestingly, the Gask Project has excavated a yet smaller rectangular enclosure beside the Roman road at Cuiltburn, a few kilometres to the southwest (Woolliscroft & Hoffmann, 2001). This too had originally been targeted as a possible fortlet but, although it produced both Roman finds and Roman style timber buildings, it proved to measure just 21.5m x 24.4m over its ditches, which anyway covered only three of its four sides. Quite what that site represents is still something of a mystery but, although Feature E is larger and does show signs of a ditch around all four sides, it is possible that it may be something similar. Alternatively, rectilinear native sites are not unknown in the area (e.g. RCAHMS 1994, 58) and only excavation can provide the final answer,

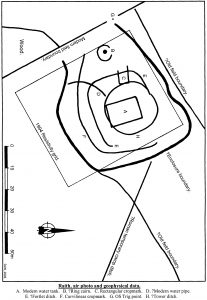

In an attempt to obtain more information, a resistivity survey was conducted in 1994 (illus 3).This was originally intended as a preliminary to excavation, but the farm changed hands shortly after the survey was completed and it has not since proved possible to regain access to the site. The survey covered an area of 50m x 60m, surrounding the 1900 water tank. (illus 4) and was conducted using a five probe Martin Clark meter and manual data recording. The meter proved to be slightly faulty in its probe balance and so the resulting plot shows a strong banding effect. This was sufficient to obscure the archaeology when using the relatively primitive plotting programs available at the time, but re-plotting with modern software (Surfer v.7) has managed to produce useful data from the survey (illus 3).

The tank itself shows strongly, as do the southern former field boundary, Ditch F and Feature B1. Most importantly, however, an entirely new structure emerged: a sub-circular ring feature (illus 4, H) which surrounds the tank (and thus the 1900 posts) and seems likely to be the long absent tower ditch. It is true that it shows as high, rather than the more normal low resistance readings, but this is a phenomenon that has been met with repeatedly in this area and seems to be caused by the ditch fills being more free draining than the surrounding clay subsoils. Amongst other sites, the Gask towers of Huntingtower and Peel were surrounded by rings of high resistance, both of which have now been confirmed as ditches by excavation (Woolliscroft 2000, 494 & 2002, 63). Certainly, the feature’s morphology is in keeping with other Gask tower ditches, many of which are also sub-circular or sub-rectangular in plan. It measures approximately 23m in average diameter, which somewhat complicates a model setting out possible building sectors for the frontier recently put forward by the first author (Woolliscroft, 2002, 18ff). Nevertheless, although fractionally the largest of the single ditched Gask towers, this is within the normal range for the system (Table 1) and all but identical to its western neighbour, Parkneuk, whose ditch diameter is 22.44m. Such a ditch circuit would also be more than capable of surrounding both a tower of the small size found in 1900 and one of the Gask towers’ characteristic turf ramparts.

The resistivity survey would thus appear to have confirmed the century old evidence for a tower at Raith and there seems little further reason to doubt its identity. It did not unequivocally detect the possible fortlet ditch and, although the aerial evidence is enough to confirm that feature’s existence, its nature must remain uncertain. The combination of geophysical and aerial data has, however, proven one thing: the two features’ ditches do appear to intersect (albeit at the point where the tower’s entrance break should lie) and the intersection is clear of the mound covering the water tank and thus accessible. This means that, it should be relatively simple to test Feature E ‘s identity and determine its chronological relationship with the tower, and it is to be hoped that excavation will be possible before too long to settle the site’s remaining problems once and for all.

Discover more from The Roman Gask Project

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.