D.J.Woolliscroft

World Heritage Status

The international importance of the Gask frontier has been obvious for some years. It is now known to be Rome’s earliest land frontier, the prototype for what became thousands of miles of similar defences around the previously expansive empire. It thus represents the start of a process that was to change the history of Europe, and a model that was to influence military science for centuries. This growing significance has now received further recognition in discussions between Historic Scotland and UNESCO that will hopefully lead to both the Gask and the later Antonine Wall becoming World Heritage Sites as extensions to the existing Hadrian’s Wall World Heritage Site. As part of this process both Directors have been co-opted onto the Research Framework Committee for Hadrian’s Wall and we will hopefully now be able to help guide developments. There have also been negotiations towards a still more ambitions plan to join with Germany and others to produce a single Roman frontier World Heritage Site, which would initially stretch right across northern Europe and, in time, hopefully further. At present, this will require a change to UNESCO’s rules. The World Heritage Site concept was developed on the expectation of relatively compact monuments, such as Stonehenge and, although there is scope for sites that straddle single national borders, truly international monuments, hundreds of miles in extent, had not been envisaged. UNESCO appears sympathetic to the possibility, however, and we hope to have more to report in future years.

Fieldwork

2003 began with another Foot and Mouth scare and we had terrible visions of a second 2001, when British agriculture and our own field program were decimated. Fortunately, it was a false alarm and everything we had planned went ahead. Our excavations at East Coldoch continued, with more unexpected results, and we conducted another of our large, whole Roman fort geophysical surveys. We continued our air photographic program, on a larger scale than ever before and continued to co-operate with local societies and individuals in field walking projects. As always, our work attracted volunteers from a wide geographical area, with diggers from Canada, the USA, and the Netherlands taking part alongside those from the UK.

East Coldoch

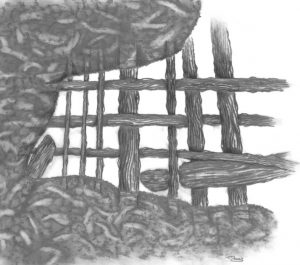

The Gask Project is primarily a Romanist organisation, but we have felt the need to turn more and more of our attention towards the natives in the last few years. It seems vital to gain a better understanding of the human and natural environment into which the Romans moved and to try to determine something of their interactions, especially given the growing evidence for a longer than expected Roman presence, which should have allowed greater complexity to develop. One of our principle research strands in this field has been our excavation at the multi-period site of East Coldoch, near the Roman fort of Doune, and July 2003 saw a further, more extended, season. From the air, the site shows a total of four superimposed structures: two palisaded enclosures, a round barrow, and a large defended homestead with a heavy penannular ditch. All of these sites overlapped, which meant that no two could have been in use simultaneously, and a lengthy occupation seemed assured. Previous seasons had established the order in which the main structures were built and also revealed that the archaeological deposits survived remarkably well, especially for a crop mark site. They also yielded wonderfully preserved environmental remains, whilst Roman bottle glass, from the defended roundhouse, confirmed Roman period occupation. The 2002 season had, however, produced major surprises, including yet another palisaded enclosure and numerous small roundhouses. The 2003 season was thus designed to examine these in more detail and continue our investigation of the complex stratified remains of the large roundhouse. We were again met by superb preservation and unsuspected levels of complexity, with the main roundhouse showing strong evidence for multiple structural periods. The 2002 season had produced evidence for continuing plough damage and so Historic Scotland granted permission for the excavated area to be expanded, by way of a rescue attempt. The results in this area were even better than elsewhere. We already knew that the final roundhouse had burned down in an event C14 dated to the 2nd or 3rd centuries. But, although there were plentiful patches of charcoal that may have come from the house’s structure, there were signs that the former occupants had sifted through the debris after the fire, presumably in an attempt to salvage any useful items, and this had homogenised the destruction deposits. The sifting was less evident in the new area, however, and so structural elements had survived rather better. In particular, several patches of carbonised wattling were found, including one piece (Fig 1) that was large enough for the (rather irregular) weaving pattern to be visible.

Elsewhere on the site, 2002’s extra palisaded enclosure was found to predate the main defended roundhouse ditch, as expected. Yet another small roundhouse was located (making six in all), which also predated the defended structure, and the remains of a so called “four poster”, thought to be connected to grain storage and/or processing, was further investigated and found to have been completely rebuilt at some point. Beneath this structure lay a large, shallow pit, filled with domestic refuse, which included quern fragments and burnt material. As is the way of such things, this was only found on the final day and so its stratigraphic position is not fully understood, but it must predate the “four poster” which itself appears to be contemporary with at least the later phases of the main roundhouse. It may prove to date to an earlier roundhouse phase, but this is not yet certain.

The biggest surprises came from an area to the north and east of the main roundhouse, which we had thought to be the latest structure on the site. Four small circular enclosures (c.5m in diameter) were found, three of which cut the backfilled roundhouse ditch and, as one was found to contain a small central pit probably for a cremation burial, they all seem likely to be funerary. We were also able to establish a stratigraphic link between the roundhouse and an infant sized long cist found in 2000 and this too proved to post-date the roundhouse. As a result, we now appear to have an alternating pattern of domestic and funerary activity, with three successive palisaded enclosures, of probable late Bronze Age or early Iron Age date, followed by the round barrow, then by the Roman period defended roundhouse and finally by a pit and long cist cemetery, built at some point (probably in the 1st millennium) after the roundhouse ditch had been filled in. At present the absolute datings remain insecure but, as before, almost all of the critical contexts produced datable carbon, which we will process at the end of the excavation.

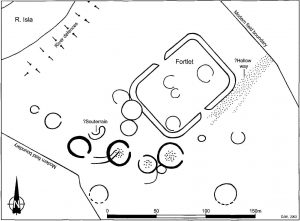

Another small ditch was found cutting the outer edge of the roundhouse ditch, some 15m to the northwest, and this might also be funerary but, whatever the case, the post-roundhouse cemetery may prove to extend significantly further than the excavated area. For three more small ring features were discovered, stretching up to 40m to the north, thanks to a radio controlled aircraft, developed by Mr Bill Kerr, which carries a remote controlled camera. The model took pictures (e.g. Fig 2) from an altitude below where we can safely fly with a light aircraft, but well above any ground based camera platform.

The results were fascinating for, although the system still had a slight vibration problem to iron out, two small ring features were clearly detectable as crop marks in barley in the next field to the north, whilst a third could be seen, much more faintly, in the pasture of the site field. Beyond these, a series of square barrows were already known from the air and we are hoping to extend the dig at least a little further to the north in 2004. In the meantime, Bill and his model will be welcome on any of our future digs and still better results should be obtainable as the system is refined.

As in previous seasons, the preservation of organic materials was superb, with grain and hazel nut shells being particularly abundant. Most of the grain was barley, but our macrofossil expert, Jacqui Huntley (University of Durham), has confirmed our field impression that wheat and oats were also present. Wheat is rare on Iron Age sites, but common on Roman installations. This could, thus, be a hint that local people changed their agricultural practices to provide the occupying army with supplies. More data will be needed before this can be stated with confidence, however. Indeed, East Coldoch’s entire cereal corpus currently presents something of a mystery. For our pollen expert, Dr Susan Ramsay (University of Glasgow) has only been able to find a single barley pollen grain from the entire site (and none of wheat and oats). Even that came from the upper fill of the main round house ditch, and so seems unlikely to be contemporary with its occupation, which leaves the origin of the cereals in doubt. The “four poster” produced chaff, as well as clean grain, which shows that cereals were processed on site, but this does not have to mean that they were grown there and it is possible that the inhabitants traded for bulk agricultural produce. This remains far from certain, however, and it would be interesting to see what pollen data from other sites in the vicinity might reveal. Cereals are self fertile and, as their pollen grains are relatively large, they tend not to travel far on the wind. Consequently, there could still have been cereal fields within a relatively short distance, especially to the east, where they would have been downwind given the area’s prevailing westerlies. Otherwise, the contemporary landscape seems to have been dominated by grazed pasture, with some alder, birch and hazel woodland (which no doubt produced the nuts). There was also heath country at a distance, which is hardly surprising for a site near the highland fringe, and remains the case today.

Cargill Roman fort

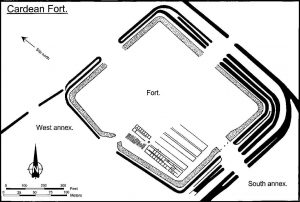

For the last three years the Project has been conducting a series of very large geophysical surveys, taking in entire Roman forts and their surroundings, and we are eventually hoping to survey most of the forts north of the Forth-Clyde line. The 2003 target was the smaller of the two forts at Cargill, on the Tay/Isla confluence north of Perth (we hope to cover the second fort in the future). The site was discovered from the air during WWII, by RAF flying instructor E.Bradley and, although invisible on the ground, it has since been seen on many occasions. Nevertheless, significant parts of its defences have never shown. Our work consisted of a 10.4 acre resistivity survey, plus a smaller (but higher resolution) 4 acre magnetometer survey. The latter was conducted as an experiment. Tr aditionally, Strathmore has been something of a no go area for magnetometry because, i.a., the magnetically noisy glacial subsoils make it hard for most meters to produce useful data. As a result, our surveys at Cardean and Inverquharity were resistivity only. But the University recently became the proud owner of one of the new FM256 gradiometers, which are reputed to cope better with such conditions and it seemed worth a try. The results more than justified the effort, with additional details revealed which had eluded both the resistivity survey and half a century of air photography.

aditionally, Strathmore has been something of a no go area for magnetometry because, i.a., the magnetically noisy glacial subsoils make it hard for most meters to produce useful data. As a result, our surveys at Cardean and Inverquharity were resistivity only. But the University recently became the proud owner of one of the new FM256 gradiometers, which are reputed to cope better with such conditions and it seemed worth a try. The results more than justified the effort, with additional details revealed which had eluded both the resistivity survey and half a century of air photography.

The late Prof J.K. St.Joseph carried out trenching on the site in the 1960s and, although the full results were never published, a brief note stated that no remains of internal structures had survived. This was borne out by the survey, indeed not even an internal road could be detected. Nevertheless, a combination of the aerial and geophysical data (Fig 3) does add greatly to our knowledge. In particular, the complete circuit of the fort’s defences was recorded, including the south gate, which had been largely conjectural hitherto.

Its internal area was 1.24 acres, almost identical to that of last year’s target, Inverquharity, and this equates to 1 heredium, a standard Roman land measure. Cargill’s shape was slightly more rectangular, but this would still seem to make the two very much a pair. Both sites lie on the borderline between large fortlets and small forts, but although we tend to prefer the former, they have traditionally been regarded as forts.

The Roman fort may have been what attracted us to Cargill but, in many ways, it was not our primary interest once there. Our work at Cardean and Inverquharity revealed significant clusters of Iron Age sites both within and, more especially, just outside the Roman defences and air photography has shown comparable sites at other Roman forts in the area. Cargill had shown a similar grouping immediately to its southwest (see cover photo), with a cumulative total of nine roundhouse like features wholly or partly visible in pictures taken by ourselves and others. The survey identified a further ten such structures, four of which lay inside the fort, and some produced extremely high magnetic anomalies, suggesting that they had burned down. At Inverquharity, we were surprised by a mismatch between the aerial and geophysical data. For almost none of the native features visible from the air were detected by the survey (and vice versa). This was not the case at Cargill, where all of the aerial discoveries showed in the survey, often more clearly than they had from the air.

Three particularly interesting discoveries emerged from the native settlement. The first was a group of four large ring features to the south and southwest of the fort, which all had unusually heavy ditches. Each showed signs of a central roundhouse and their primary interest to us is the fact that they seem to present parallels for East Coldoch, which had hitherto appeared to be unique. East Coldoch’s ditch diameter is slightly (2m) bigger than the largest of the Cargill group, but its air photographic and geophysical signatures are otherwise identical.

The second finding may appear rather trivial but was interesting, if only because it flies in the face of currently accepted wisdom. In recent years something of an orthodoxy has grown up that roundhouse entrances always, or at least generally, face towards the east or southeast. This may have a perfectly functional explanation, since an easterly orientation would shelter the entrance from the prevailing westerly winds. Some, however, prefer a more ritualistic interpretation and assume that the entrances were oriented towards the rising sun for religious reasons. In fact the two need not be mutually exclusive. Human societies frequently generate rituals and taboos to reinforce advantageous behaviour and discourage folly. It is, after all, perfectly sensible for us to avoid walking under ladders in case the fool at the top accidentally drops something, and it is equally possible that a ritualised orientation of roundhouses to face the sunrise might still have its origins in a desire to avoid the worst effects of winter gales. The sunrise is, after all, a far more frequent occurrence and so easier to use as a reference. Whatever the case, however, a significant number of the Cargill features have other entrance orientations, including two that point north and northwest.

Finally, a curved structure was detected to the west of the fort which consisted of two narrow bands of high resistivity readings that joined in the northeast and contained an interior area of low readings. This would suggest a stone lined cellar like structure and the farmer informs us that stones have been ploughed up on the spot. The western end of the feature was obscured, but the visible trace was 20m long and c. 3.9m wide. It cannot yet be proved, and the interior may be thought a little wide, but this seems likely to represent a souterrain, one of the large underground storage structures so characteristic of the Roman period Iron Age in this region. If so, the normal stone roofing slabs are probably missing, as these would have produced high readings for the interior as well. Ian Armit has recently suggested that souterrains may be linked to Roman supply provision and so it may be significant that both Cardean and Inverquharity have also produced such structures.

There is clearly a limit to what remote sensing can do and we still have no way of determining the relationships between these settlements and their forts. Obviously the internal features cannot be contemporary with the military occupation and it is possible that the settlements either date to a totally different time, or that they were ejected when the Romans arrived, so we do not yet know whether the two interacted significantly. Moreover, even if parts of the settlements were occupied at the same time as the forts, it is still possible that the two merely glowered at each other across the defences. Indeed the forts may have been deliberately set to keep an eye on local population centres. Given the souterrains, however, it is tempting to wonder whether the settlements might have grown up around existing forts, perhaps attracted by their economic potential. They might even have acted as an equivalent to the more Romanised vicus settlements which are found outside Roman forts further south, but are so far conspicuously lacking over much of Scotland. Either way, it is possible that the internal roundhouses represent native reuse of the defensive circuits after the Romans had departed.

During the survey, the Perthshire Society of Natural Science carried out fieldwalking on the site. The results were particularly interesting given the possibility of native style vicus activity because, although a number of Roman finds were recovered, none of them came from the fort. Almost all of the material came from the settlement or the slope between it and the river. The only exception was found well to the south of the fort. This was a Roman period Iron Age terret ring of a type usually only seen in southern England. The find is currently with Fraser Hunter of the National Museum of Scotland, who is preparing a report, but he informs us that only one other example has ever been found in Scotland. This came from the Roman fort of Newstead, near Melrose and, as it seems possible that both pieces found their way north with the military, it is tempting to wonder whether auxiliary soldiers of British origin could have been involved. Auxiliaries are usually thought to have been stationed well away from their province of origin, for security reasons, but although this is certainly true of whole units, local recruiting of individuals may still have been practised.

The fieldwalking also produced a small mystery from more modern times, for the site yielded a significant number of lead musket balls (plus a few smaller pistol balls), by no means all of which had been fired. We have been unable to find any record of a battle of any kind taking place in the field, so it may just have been used as a practice ground. If so, however, the shot shows a very even distribution, with no sign of regular butt and firing point locations, and it seems strange that target shooters should be so careless with unused ammunition. Lastly, the field walkers recovered quite a collection of modern coins, but these too were rather odd, since almost all dated to a single decade: the 1860s. These were of small denomination, mostly farthings and ha’pennies, and our initial assumption was that the field had been used as a work camp during the construction of the (now disused) railway to Stanley, which runs immediately to the south of the field. This was apparently built in the 1850s, however, and so the abnormally tight date range remains a puzzle.

Air Photography

2002 was a disappointing crop mark year and so we conserved much of our flying budget. As a result we were able to make good use of a glorious sunny spell in January 2003, which mixed a light dusting of snow with strong, low angled light. The result was three (cold) flights into a treasure trove, along the Highland fringe, the Ochils and Sidlaws. Numerous normally invisible surface features were picked out by the conditions, ranging from the prehistoric to the relatively modern. Many of these were previously unrecorded, but even well known sites such as hillforts were picked out with a degree of detail that is normally unobtainable. One of the most notable features was the height to which cultivation reached in the past. Settlements with extensive rigg and furrow cultivation were located at altitudes which are now used only as rough grazing and even north facing slopes could have cultivation remains right up to summits of over 1,200′. Thaw marks also produced useful new data, with the internal road system of the Roman fort of Dalginross showing better than it does as a crop mark, and it is to be hoped that similar flights can be made in the future.

The summer was hot and dry, but with a wet spell just before the crops began to ripen. As a result, we had a reasonable cropmark season, but not quite the bonanza we had hoped. Nevertheless, quite a number of discoveries were made in the course of three flights: ranging from roundhouses, to a length of (possibly Roman) road between the two Cargill forts, to an odd square enclosure beside the A90 at St Madoes. Potentially the most important site, however, was a large (c. 3.5 acre) rectangular enclosure (Fig 4) which looks very like a Roman fort. It has rounded corners and what appears to be a double ditch and, although we cannot yet confirm this identity, it should be well worth keeping an eye on in future.  Certainly, we will make sure we fly over it again and we plan to undertake one of our large geophysical surveys on the site at some point, probably in 2005. Of course, the discovery of any new Roman fort in our study area would be significant. They are, after all, increasingly rare discoveries, with the last one, Doune, found 20 years ago in 1983. This site, though, if real, has the potential to completely change our view of the strategic picture of Roman Scotland, for it lies near Collessie in Fife. Current maps of Roman Fife are a complete blank because, although three temporary camps are known, no permanent installation has ever been found. This is usually explained by suggesting that the inhabitants were Roman allies and so did not require watching, but there is no other evidence to support this hypothesis and the site desert may just be an accident of discovery. The noise of unhatched chicken counting now becomes deafening but, if the site is a fort, it lies on a low but easily defended ridge and occupies a perfect strategic position. For it sits at the crossing point between two of the main east-west and north-south routes across the peninsular: the A91 to Cupar, and the route from Kirkaldy, past Lindores Loch to Newburgh and the Roman fortress of Carpow. Archaeologist are often asked why we repeatedly re-fly air photo targets. This site provides an answer, whatever it turns out to be, for there a number of prehistoric settlement sites in the adjoining fields and the field has been photographed many times before . Yet, neither the possible fort nor a smaller square enclosure, that sits on a different orientation inside it, have ever been seen before.

Certainly, we will make sure we fly over it again and we plan to undertake one of our large geophysical surveys on the site at some point, probably in 2005. Of course, the discovery of any new Roman fort in our study area would be significant. They are, after all, increasingly rare discoveries, with the last one, Doune, found 20 years ago in 1983. This site, though, if real, has the potential to completely change our view of the strategic picture of Roman Scotland, for it lies near Collessie in Fife. Current maps of Roman Fife are a complete blank because, although three temporary camps are known, no permanent installation has ever been found. This is usually explained by suggesting that the inhabitants were Roman allies and so did not require watching, but there is no other evidence to support this hypothesis and the site desert may just be an accident of discovery. The noise of unhatched chicken counting now becomes deafening but, if the site is a fort, it lies on a low but easily defended ridge and occupies a perfect strategic position. For it sits at the crossing point between two of the main east-west and north-south routes across the peninsular: the A91 to Cupar, and the route from Kirkaldy, past Lindores Loch to Newburgh and the Roman fortress of Carpow. Archaeologist are often asked why we repeatedly re-fly air photo targets. This site provides an answer, whatever it turns out to be, for there a number of prehistoric settlement sites in the adjoining fields and the field has been photographed many times before . Yet, neither the possible fort nor a smaller square enclosure, that sits on a different orientation inside it, have ever been seen before.

In addition to our pictures, local flying instructor Sandy Torrance has again been kind enough to send photographs taken during his own flights, which give us vital coverage at different times of year. These too contained their fair share of new discoveries, including a fascinating c. 1 acre enclosure, beside the Tay near the Inchtuthil legionary fortress. Above all, however, Sandy seems to have a gift for finding Iron Age style sites around Roman forts and this has added significantly to our own, largely geophysical, research in this field. Already in 2002, he had added native sites in and around Carpow, but this year has brought two new roundhouses at the fort of Bertha, another two at Cardean (to add to those we found in 2001) and another at Cargill, whose existence was confirmed only weeks later by our geophysical survey. This is an impressive record for a single year, and long may it continue. Between us, the Project took close to 2000 air photographs in the year, more than ever before. All have now been digitised and they are currently being catalogued. Once this is completed our normal CD-R sets will be distributed to the Project’s members and sponsors, as well as other interested bodies, such as the NMRS and the Perthshire SMR

As in previous years, our own flights were made from Scone, and we are again immensely grateful to Bill Fuller for volunteering his services as pilot. Bill’s archaeological eye and vast flying experience have always allowed the maximum value to be gained from our flying time, but this year he has also turned photographer: courtesy of Santa and a very nice digital camera. We had always felt a little sniffy about the image quality from such gadgets in the past, but this one’s results were impressive enough that we have since had another good look at the market. After all, the Gask Project routinely spends more than Ł1,500 a year on film and processing and so digital photography would soon become cost effective, despite the monstrous prices still charged for really high end cameras. As yet, however, we remain unconvinced that the technology has quite equalled really good film cameras, despite constant claims to the contrary, especially given the big enlargements often needed with aerial shots. Moreover, like many archaeologists, we worry about the long term permanence of the images, in a discipline which has always accepted the duty to produce archivally permanent records. We regularly use photographs taken 60 or more years ago, including the odd one taken in the 19th century, and digital files have yet to prove that they can last in this way. For the moment therefore, although digital is certainly a useful supplement to film, our dark room looks set to stay open.

Collaborations

The Gask Project has again been able to work with a number of other workers to gain additional information from our own sites and those of others. Some of these have already been mentioned, but we have also worked with lithic specialist Abi Finnegan, pottery experts Alan Vince, Felicity Wild, John Dore, Catherine McGill and Kay Hartley, and with quern expert Ewan MacKie. We have also co-operated with Patrick McGannon, a postgraduate in Military Studies, on a Staff Analysis of the Flavian deployment in northern Britain, and with the RCAHMS on a terrain survey at Cardean.

As in previous years, gamekeeper, Mr W. McIntosh, very kindly sent us material picked up on fields around the east end of the Gask Ridge, and this year’s haul included three fascinating coins. The first came from the small temporary camp of East Mid Lamberkin. We conducted some trenching and geophysical work on this site some years ago, but the only dating evidence was a Pictish period C14 date from the fill of a secondary ditch re-cut. This was interesting in that it showed Dark Age reuse of a Roman fortification, but it did not help to date the camp’s original construction. Mr McIntosh’s coin was Vespasianic, which suggests a Flavian date contemporary with the Gask frontier. Moreover, the coin dated to 71 AD, very early in the reign and, as it was lost in an unworn condition, it had not been in circulation long when lost. It thus adds yet another hint to the growing evidence that the Romans may have reached the area rather earlier than we had thought.

The other two coins were rather curious. They were found a few hundred meters apart in fields around the village of Forteviot, and about 1 km to the east of the large temporary camp of the same name. The first was an ancient copy of a dupondius of the Emperor Claudius. These seem to have been manufactured in large quantities in early Roman Britain, possibly officially, because of a shortage of genuine small change, but they went out of use fairly quickly and this example was little worn. Our coin expert, Prof David Shotter, tells us that it is unlikely to have been lost later than the early 70s AD, if not earlier. This again points to early occupation, but the second coin was even more of a surprise. It was another (probably official) ancient copy, but this time of the short lived third century Emperor Claudius II (268-270). No Roman activity is known in Scotland at this period, but Prof Shotter tells us that the coin is unlikely to come from a modern collection. It may have reached the area through trade, but it had been lost in very worn condition and so had circulated for some time before reaching Forteviot. It is thus just about possible that it did reach the area with a Roman army. Historical sources mention a number of campaigns in Scotland in the early 4th century, but neither the texts nor current archaeological data provide any detail and we have almost no idea of the scale and reach of this activity. One coin is obviously very flimsy evidence on which to reconstruct an entire war, but it may be a small hint that at least one of these campaigns reached as far as Strathearn.

Stormont Loch

As reported last year, Dr Hoffmann is co-operating with Fraser Hunter of the NMS to report on a Roman bronze trulla (field canteen) found near Stormont Loch and now in Perth Museum. The pan is Roman military equipment, but X ray analysis of the copper rivets used in repairs suggests that it later came into native hands. It has generally been assumed that the trulla was thrown into the loch as a votive offering, but it was actually found on dry land. The loch has contracted substantially over the last two centuries, however, thanks to drainage works and, in addition to study of the piece itself, a great deal of archive work has been done to establish the loch’s original size. The results suggest that the piece was never in the loch and may be a normal archaeological loss. The report is now almost complete and should be submitted early in the new year.

Archive Work

Since its foundation, the Project has been involved in tracing and publishing earlier work, whose instigators were unable to publish their results themselves. As part of this program, Birgitta has spent the last two years writing up the late Prof A.S. Robertson’s large 1960s and 70s excavations at the fort of Cardean. 2003 saw the completion of her huge, book length (more than 400 page) report which should be published in 2004. The results have been fascinating and unexpected, although the work was hindered by the poor state of the records. Cardean is the third most northerly Roman fort known, lying as it does near Meigle in Strathmore. It dates to the Flavian period and, on the conventional dating model, it should only have been in use for perhaps 2 years.

Yet all of the major excavated buildings (Fig 5) had been rebuilt in service and there are signs that, at least, parts of the defences were also refurbished. Other contemporary Roman installations in the area, particularly the larger of the two Cargill forts, also saw major modifications in service and we have long had a similar pattern further south on the Gask frontier. Cardean, thus adds further support to the ever growing evidence that the 1st century occupation was longer than had been thought.

The fort was exceptionally large, at around 8 acres, and may have held some sort of combined force, rather than the usual single auxiliary unit. Whatever the case, there is evidence that at least part of the garrison was cavalry, partly because there were plentiful finds of horse equipment and partly because a series of pits were found in the front rooms of the barrack contubernia, which are now widely seen as a mark of stable accommodation. The site also had two annexes and a re-examination of the available aerial data has shown that the western example was larger than had been thought. The fort sits on a raised promontory between the Isla and its tributary the Dean Water, but the annex now seems to extend down to lower ground near the ancient confluence and may well have held a landing area for waterborne supplies. The work also shed light on more modern usage of the site, including the rediscovery of a former mansion with possible formal gardens and what may be 19th century industrial activity linked to the construction of the nearby (now disused) railway to Alyth.

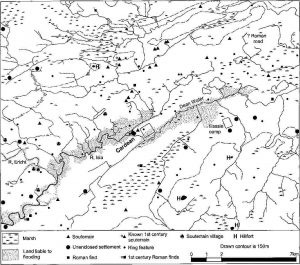

One of the most interesting aspects of our own work on Cardean has been a survey of native activity and the environment within a five mile radius of the fort (Fig 6).

Only a few local Iron Age sites survive as surface features, but we have been through every known air photograph and the result has been literally dozens of sites, some of which were appreciable settlements. At the same time Birgitta has gathered an impressive haul of environmental data. Direct evidence from excavated sites has proved scarce, but it has still been possible to reconstruct the natural environment using medieval records of the former Cistercian abbey at Coupar Angus, and estate records and other accounts dating to before the great rush of agricultural improvements in the 18th century. Soil data has been studied from modern surveys, whilst flood patterns and old river channels have been mapped from historical accounts and by flights over modern floods by ourselves and Sandy Torrance. In last year’s report, when this work was still at an early stage, we quipped that although the 20th century may have been stupid enough to build in flood plains, the Iron Age was not. At the time, however, we had little idea how precise the correlation was to prove. For, although virtually no Iron Age sites could be found in the areas our environmental work reconstructed as wetland or liable to flood, many were placed right at the edges of the dry ground, as close to a water source as they could afford to get.

Cardean’s strategic setting is far from obvious today, but it too makes sense in the light of the landscape survey. Strathmore now holds some of the richest farmland in northern Scotland, but the pre 18th century picture was very different. Vast areas of what is now plough land were then marsh. There were many lochs which have since been drained altogether or significantly reduced in size, whilst the rivers Dean, Isla and Ericht regularly flooded much greater areas than they do today. In this environment, dry, productive land was more restricted and so were movements along the valley. In fact, Cardean guards the point where a strip of dry ground along the southern strath (which also carries Eassie temporary camp) meets a dry route running north towards Alyth. This, in turn, links to a similar dry strip along the northern side of the strath (which is still marked by a series of much older standing stones), making the fort the key to the whole area. Interestingly, this fits well with the evidence for cavalry. For full exploitation of this advantage would have needed a high speed, long range patrolling capability. In fact, there is evidence from all over the Roman Empire that forts set in and around wetlands tended to have cavalry garrisons. In the past, this has always seemed counter intuitive, since swampland is hardly good cavalry country, but the detail possible with the Cardean survey could provide an explanation. Because many wetlands contain passable route ways and the Romans may have found cavalry the best way to ensure that all could be covered.

In addition to the Cardean work, we have been working on two other archive finds. The first are records of the Roman Gask road and more specifically the repairs and re-routings to which it was subjected in the early modern period. These are interesting in their own right and should help us to determine how much of the remaining fabric is Roman or even to trace missing sections.

The second is a small but fascinating collection of photographs donated by Dr D Emslie-Smith. These have provided views of Inchtuthil before it was landscaped for its brief time as a golf course, and show clear signs of the individual dump deposits left in the ditch when the rampart was slighted on abandonment. They also show views of the surviving defences of Kirkbuddo temporary camp after a gale in the 1950s had temporarily removed the tree cover that now makes it difficult to photograph well. The most important material, however, was a set of pictures taken in 1939, whilst the donor was working as a schoolboy volunteer on the late Prof Ian Richmond’s excavation at Fendoch. Fendoch has long been seen as the archetypal short lived, single period, Flavian fort and a plank of the traditional, very short chronology, dating. But, the famous published plan is largely conjectural, being reconstructed from a series of small trenches, and Richmond’s own photographs show tantalising hints that some of the internal buildings had been repaired or rebuilt. The only firm evidence, however, is Richmond’s admission that one of the rampart ovens had been rebuilt. Of itself, this need have no real significance for, if badly constructed, the feature may have needed repairs almost immediately. But Dr Emslie-Smith’s photographs show part of another oven right next to the two phased example (Fig 7), which would have overlapped it had the two been contemporary.

This suggests three phases, which is a lot more suspicious, and although it cannot prove the case by itself, it does hint that Fendoch may show the same more complex (and probably longer) history as all the other northern installations for which data is available.

Publications and Publicity

2003 has seen a number of Gask Project publications. Birgitta co-edited the proceedings of the 18th International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies, held in Jordan, in 2000. The book runs to almost 1,000 pages, published in 2 volumes by BAR and, although the printed date is 2002, it actually came out this January. Apart from the editor’s credit, both Directors had papers in the book: David’s is a report on the Project’s results since the previous Congress in 1997 and Birgitta’s deals with the rampart buildings of legionary fortresses, including the Scottish site at Inchtuthill. Birgitta also published an account of recent work on Roman Scotland, in “The Archaeologist” and a comparative study of Roman glass from northern Britain, in the proceedings of the 15th congress of the Association Internationale pour l’ Histoire du Verre. Meanwhile David’s detailed interim report on our East Coldoch excavations went out as (the shape of things to come) a Web publication. In addition, we had the usual short notes in “Britannia” and “DES” and our web master, Peter Green, has continued to do a wonderful job of updating our web site.

The year has also seen quite a quantity of work submitted for publication. The most significant was, of course, Birgitta’s book on Cardean, but she has also submitted an article on Tacitus for a Routledge collection called “Archaeology and Ancient History: Breaking the Boundaries” and a paper on the dating of the Roman bronze skillets from Perthshire for “Lucerna”, the journal of The Roman Finds Group. At the same time David submitted reports on our big aerial and geophysical surveys at Raith on the Gask frontier and the fort of Inverquharity, both of which went to PSAS. 2003 also saw the 19th International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies, this time held in PéWcs in Hungary, and both Directors gave papers. David’s described our new evidence for Roman/native interactions in Scotland, whilst Birgitta detailed her landscape survey around Cardean, and both will be published as part of the proceedings. We have also continued to attract media interest. The Scotsman wrote about us in February and “British Archaeology” published a lavishly illustrated article on our work in April. Even the “Kent Archaeological Review”, which (we confess) we had not previously heard of, published a paper on our work. The year also saw repeats of two of our TV appearances: on “Time Fliers” and “What the Romans did for us”, and the BBC have shown an interest in our discovery of a possible major country house at Kinclaven for a mooted future series of “Time Fliers”.

As ever, the Directors have continued to give lectures to a variety of academic, student and amateur bodies and a number of local societies visited the Coldoch excavation. Birgitta gave a paper at the Military Studies Centre in Chester, whilst David gave talks in Perth, Wigan, Dunoon, Paisley and Manchester, and also addressed the annual joint session of the Roman Society and Classical Association at the University of Edinburgh. Both Directors gave papers to the annual Roman Army School at the University of Durham, with David reporting on the Project’s evidence for a longer than expected 1st century Roman occupation of Scotland, and Birgitta presenting a new analysis of Tacitus’ “Agricola”.

Sponsorship and Acknowledgements

The Project continues to be sponsored by the Perth & Kinross Heritage Trust, whose support has been indispensable and much appreciated. In 2003, the Trust funded our air photographic flying program, the purchase of additional air photographs and almost all of our specialist reports for sites other than Cardean. Their original funding period expired this year, but we are delighted to report that the Trust have renewed their support for a further three years, for which we are deeply grateful.

In addition to this long term funding, we must also express our gratitude to three more bodies. Historic Scotland are both funding and publishing the Cardean report. The Society of Antiquaries of Scotland funded our excavation at East Coldoch, and our long standing corporate sponsor (which continues to insist on anonymity) has again provided material support, mostly in the form of loaned computer and imaging equipment.

The Project continues to owe thanks to Dr David Simpson, who again provided medical services during our fieldwork, to Mark Hall of Perth Museum and to Mrs H.Fuller, for spoiling us rotten whenever we go up to fly. Andy and Eleanor Graham continued to provide muddy diggers with accommodation and, as always, we are more than grateful to our many field volunteers, especially our wonderful trench supervisors: Keith Miller and Phil Broadbent. We are particularly grateful to the farmers and land owners who allowed us access to their sites, and must also say a special thank you to Ruth Dundas, Archie Dick and Birgitta’s long suffering postgraduate, Patrick Hurley, who were dragged onto the Cargill survey at the eleventh hour when others let us down. Finally we thank SUAT and Geoscan Ltd who, for the second year running, leapt to our aid when we suffered a broken resistivity probe. This could have led to several wasted days, but the former lent us a replacement meter on zero notice, whilst the latter had a replacement part rushed to Scotland, so that the eventual time lost was only a few hours. As we write, Geoscan are building us a second probe array to act as a spare, so this should never happen again.

The Future

2004 should be another busy year for the Project, with a number of ventures in preparation. In the field the year should be our busiest ever. As before, one key event will be the excavation at East Coldoch, with another slightly longer than usual season planned. This should be our last on the site but, knowing its capacity for surprises, one can never be entirely certain. We also have another, rather smaller, excavation planned to coincide with Perth Archaeology week. This will investigate a deep and obviously artificial cutting that has long been known to lie immediately south of the grounds of Innerpeffray Library. Local lore has it that this represents the Roman Gask road coming up towards the Gask Ridge from its crossing of the Earn. There was a Medieval ferry in the area, which might also have used the cutting, but a Roman origin is certainly plausible. The Earn has created a series of river cliffs in this area and the cutting reaches the water at the only spot for some distance up and downstream where both banks are low. There are also aerial traces of the Roman road heading from the fort of Strageath towards the opposite bank at this spot. As a result, we have had our eye on the feature for some years and it will be good to have the opportunity to get a proper look at it.

For the last three years our geophysical program has covered one entire Roman fort per year. When we began the series, we were told by a number of experts that even that was impossibly ambitious, because we insisted on using resistivity as well as magnetometry, which is a much faster technique. This year, we plan to stick our necks out still further and attempt to cover two forts. The work will be done in combination with Susie Moore and David Hodgson, now postgraduates in geophysics at the University of Bradford, who have worked with us for years. The first survey has already been arranged for the fort of Drumquhassle. We hope that the second will be at Fendoch, but this is still being organised.

Finally, our air photographic program will continue and, as always, we pray for a good cropmark season. Failing that, however, our new funding arrangements have been made more flexible as to when we need to spend a given year’s money, which means that it will be easier for us to switch time to winter shadow flying in the hills, or soil mark flying during the ploughing season.

Out of the field, the Cardean report is scheduled to be published during the year and other reports will appear or not according to journal schedules. Meanwhile, Birgitta’s book on the glass of Newstead fort should be completed during the year, with its wider survey of glass in Roman Scotland. The Cargill survey should be submitted, as should an updated Coldoch interim and, as always, the web site will be kept up to date. The Project has also been commissioned to write two further books. The first is a tourist guide to the Romans in Perthshire for our sponsors the Perth & Kinross Heritage Trust. This will be a 20-30 page booklet to be published in 2004 and is already well in hand. The second is a full length book for Tempus, on the Romans north of the Forth and Clyde. This is not due to be submitted until 2005, but work will begin this year. We hope that the book will replace, or at least update, the late O.G.S. Crawford’s wonderful, but now long out of print, 1949 work “The Topography of Roman Scotland North of the Antonine Wall”. This has never been matched by any modern account for sheer archaeological detail and we aim to make good this deficit, although we do plan a slightly snappier title: “Rome’s First Frontier”.

Finally, the Directors will continue to give public lectures wherever invited. Six have already been booked, including (for the second year running) papers by both of us to the Roman Army School, and others will no doubt be scheduled as the year progresses.

D.J. Woolliscroft and B.Hoffmann

Directors: The Roman Gask Project

University of Liverpool

Discover more from The Roman Gask Project

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.